I was first a whitetail hunter. I took my North Woods knowledge and tried to apply it to elk. It turned out to be a blessing and a curse.

For seven years after I moved to Montana, I hunted elk like a man possessed. My freezer was like a gleaming white coffin for my dreams of that first bull. How could someone so committed to elk hunting, in the most fit years of his life, with a lifetime of hunting experience struggle so mightily to find even one wapiti with the mandatory 4-inch brow tine?

After a frenzied search for the key to elk success, I grew frustrated. I abandoned my quest for elk and returned to hunting whitetails so I could fill my freezer. I knew whitetail hunting. I grew up hunting them in the North Woods of Minnesota. Even out here in this vastly different landscape, it was intuitive. Nice bucks seemed to find their way to my bullets. So why not elk?

In an effort to understand why I excelled at whitetail hunting and failed to connect with elk, I wrote down everything I did right to make me a successful whitetail hunter, to see if it would show me the path to bull elk. Surprisingly it did. I realized that while I was studying the best strategies and equipment, I had passed over the fundamentals of elk themselves. What they eat, where they seek shelter, how they react to pressure from predators, and where they go when the seasons and weather starts changing.

I had learned all this stuff about whitetails and walleye intuitively because I grew up chasing them. I understood their seasonal needs and patterns. Knowing the preferences and tendencies of mature bucks, I didn’t spend a lot of time thinking about the latest call or rattling technique or scent cover. But I did spend time sitting motionless in the places where those bucks were most likely to be. Unfortunately, when it came to elk, I didn’t have a clue.

After experiencing this epiphany, I spent the whole rest of the summer reading. Elk behavior and habits are not common topics in today’s hunting books, even rarer in hunting magazines. Instead, they focus overwhelmingly on tricks and tools. So I turned to books of biology. Elk Country, by Valerius Geist, was a great asset, and Elk and Elk Hunting by Hart Wixom had more good information than I could absorb. A lot of fine articles on elk biology and elk behavior have also appeared in the pages of Bugle.

I began to realize that elk, like all animals, have specific needs based on the time of the year, and those needs affect their behavior. Feed, cover, and water are always on the needs list, with mating being a seasonal attraction that affected the previous three.

By the time opening morning rolled around on my seventh elk season in Montana, I was filled with anticipation, but also something new: confidence. My research told me that late-October bulls were going to be in post-rut mode, holed-up in tough spots where hunters did not want to go, where water and even marginal food could be found. Having identified such places on my maps (this was before Google Earth), I plotted my path. I would go where the elk wanted to be, at the time of year they wanted to be there, in terrain most hunters avoided.

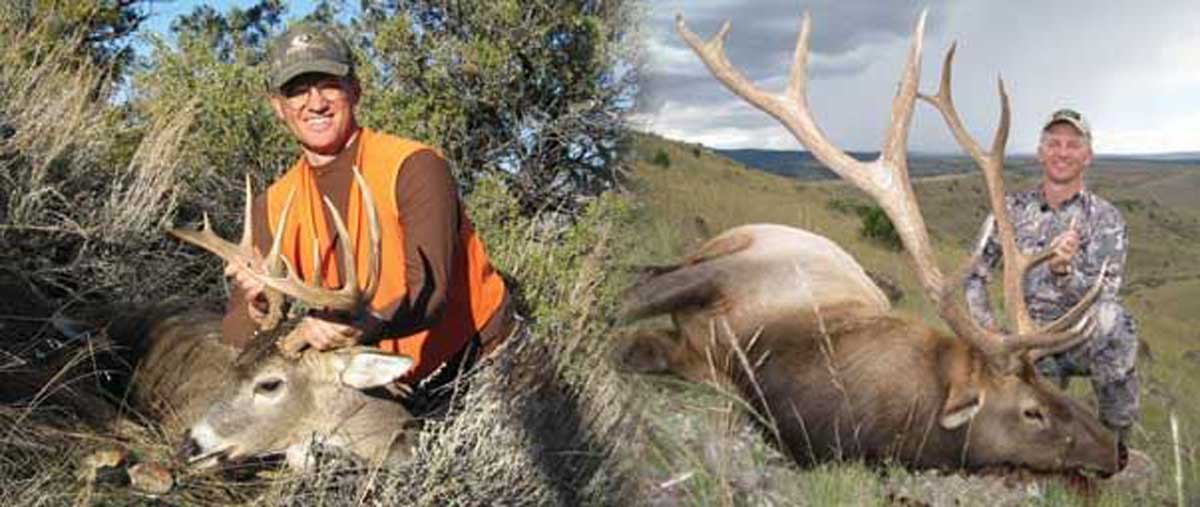

I slept in my truck at the trailhead, and an hour-long climb in the darkness got me where I needed to be. By 10 a.m. on the very first day of the very next season, I shot my first bull. With only five slender points on the largest beam, his rack still hangs in my shop as one of my greatest hunting accomplishments. Not because I killed a bull, but because I overcame what I had convinced myself was impossible.

Now, 12 years later, I produce a hunting TV show called On Your Own Adventures. All hunts take place on land open to you and me, without the helpful assistance of guides, and the great majority of the hunts are in country I have never hunted. When we go to film an elk hunt, we need to quickly sort out what those elk are doing and where they’re doing it. Only then do we worry about what tactics and tools to use.

How Whitetails Brainwashed Me

Most of the mistakes I made on elk had their roots in my whitetail days. I took whitetail’s routines and habitual patterns and transferred them to elk, when in reality, none existed. I expected elk to feed in the morning, bed during the day, and come out again in the evening. Elk don’t do that. I also expected elk to follow a habitual routine from day-to-day. Elk don’t do that either.

One of my favorite whitetail tactics is to find smaller parcels of habitat and hunt there, knowing they are often overlooked by other hunters. I spent many elk days hunting a 100-acre piece here, another 250-acre piece there. No elk. Whitetails will hunker down and wait hunters out. Elk just plain leave. Even if there is a small piece of ideal habitat, if the elk feel too pressured, they’re gone.

I could stroll to most of the places where I killed good whitetail bucks in half an hour.,. Consciously or not, when I took up elk hunting I limited myself to safe “dragging distance”—the zone where I could easily get one out of the woods. This assured that I never had to worry about such a chore.

When I finally harvested my first elk, I realized the amount work that lay ahead of me. Although I struggled through the daunting task of gutting and packing out my first elk alone, it has turned into a repeatable pattern.

To date, all but one bull has required game bags and a backpack. I have since invested in a great pack and the basic gear to convert a bull into manageable pieces. But my best equipment is the confidence that a middle-aged guy like me can handle the quartering and hauling process. No it is isn’t easy, but it’s plenty doable.

Whitetail hunters need to get comfortable with the idea that to shoot a bull, your best bet is going to be in the tough places. That terrain will give you the most discomfort when you imagine retrieving an elk from that spot. But, you are hunting for a bull, so go look where he’s most likely to be. If it takes you two days to quarter and get him to the trailhead, what else did you plan on doing for those days? Consider it time well spent.

How Whitetails Prepared Me

Hunting whitetails has taught me many tactics that work on elk. There is no other hunting I can think of that better prepares one for elk hunting than still-hunting and tracking bucks in the North Woods. Little did I know that what I learned there in the spruce swamps would help me kill bull elk on a consistent basis once I finally went where they lived. Those swamp bucks had already taught me how to get on a track and follow it quietly and patiently, constantly scanning ahead.

Meandering whitetail tracks in fresh snow told me they were ready to bed down, and I would come to realize this is the same for elk. Having followed a group of bulls across a steep face in the Madison Range, the line of tracks suddenly split and dispersed. I shot one of those bulls as he stood from his bed. I smiled, thinking how similar it was to a whitetail track I had followed years earlier with similar results.

Whitetails also taught me how to be sneaky. The careful heel –toe step has allowed me to get astonishingly close to massive bulls. But the most important lesson whitetail deer have taught me however, is always work with the wind. Once a big bull catches a whiff of you, he’s gone.

My point to all this is—don’t be afraid to study, adapt and learn. Sure you’ll make mistakes. But that is part of the fun. Progress is not just learning what worked and why, but what didn’t work and why not. Any whitetail hunter can become a successful elk hunter. Just start by learning all you can about the animal. That will tell you where to find them. Once you find them, use that elk knowledge to sort out the best strategy. Biology may not be glamorous, but really knowing your prey is deeply fulfilling. It has a way of filling your freezer, too.